blogs

Circular Economy is here to stay – Building resilience while transitioning to circularity

The circular economy can play an important part in building resilience to future crises, to survive shocks and live through disruptions such as a pandemic, water scarcity, or other climate change related crisis. However, before we dive into building resilience while transitioning to circularity, we will dive deeper into the concepts of circularity and the circular economy.

The birth of circularity

Concepts linked to circularity, such as closed-loop systems, waste management, industrial ecology and product recovery management, started to arise in the academic world in the 1990’s. Allegedly, the first international academic workshop about re-use was hosted at Eindhoven University of Technology in 1999 (Flapper, 1999). The term Circular Economy (CE) only gains attention in academic publications from 2010 onwards. In addition to the concepts mentioned above, there are several schools of thought related to circularity, each typically connected to their intellectual founders, as described in e.g. Webster (2017) and Weetman (2017):

- performance economy, based on the work by Walter Stahel

- biomimicry, based on the work by Janine Benyus

- blue economy, based on the work by Günter Pauli

- regenerative design, based on the work by John Lyle

- cradle-to-cradle, based on the work by Michael Braungart and Bill McDonough

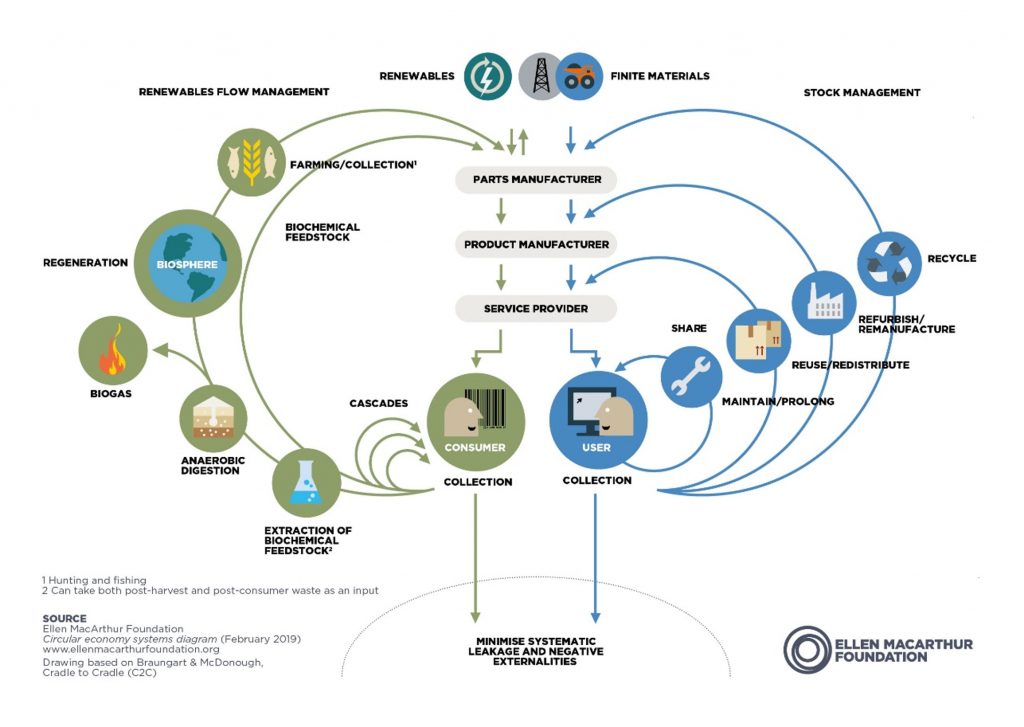

The cradle-to-cradle school of thought is seen by many as a conceptual breakthrough in the maturity of circularity. It has been the main inspiration for the famous butterfly model of circularity popularised by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The diagram illustrates a system of continuous flow in a value chain, in which two cycles are distinguished, each centred on different types of materials: the biological cycle (focused on biological materials, e.g. wood or food) and the technical cycle (focused on technical materials, e.g. metals or polymers). The biological and technical materials are in need of different reuse processes; therefore, they need to be collected separately after use to be able to flow back into their respective cycles.

The rise of circularity

A large number of different factors explain the recent boom in attention for the circular economy. Roughly speaking, they can be summarised under two headings: society pull and enabler push.

Society pull reflects the underlying problems of climate change, resource scarcity and global instability. The top five global risks in terms of likelihood, identified in the Global Risk Report, are all environmental (World Economic Forum, 2020):

- extreme weather events;

- failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation;

- human-made environmental damage and disasters;

- major biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse; and,

- major natural disasters.

In addition, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (2019) released their first assessment on how ready the world is for a global emergency. Their verdict? Not ready: “For too long, we have allowed a cycle of panic and neglect: we ramp up efforts when there is a serious threat, then quickly forget about them when the threat subsides. It is well past time to act” (p.9). While governments and businesses are cautiously going ‘back to normal’, both the Global Risk Report and the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board point out that ‘normal’ is largely the cause of the climate crisis and the collapsing of ecosystems. Various stakeholders in society, such as citizens, businesses, non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) and governments, are addressing these issues more and more actively, creating society pull.

The enabler push reflects elements that facilitate an effective way forward, such as innovative developments in terms of technologies, business models and circular strategies or regulations and incentives. It is becoming very clear that due to increasing society pull, circularity is now firmly on the agendas of policy makers, academia and NGO’s. On the business side of things, the recent increase in attention for the circular economy has led to an important increase in corporate, consultancy and entrepreneurial activity related to the topic.

The definition of circularity

In Mastering the Circular Economy, we use two definitions as practical backbone for the book. We refer to the circular economy as a wider, more global and more generic concept, whereas we will use the term circularity when referring to the more specific (micro) context of a single company:

- Circular economy: an industrial system that is restorative and regenerative by intention and design. It replaces the ‘end-of-life’ concept with restoration, shifts towards the use of renewable energy, eliminates the use of toxic chemicals, which impair reuse, and aims for the elimination of waste through the superior design of materials, products, systems, and, within this, business models (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2012).

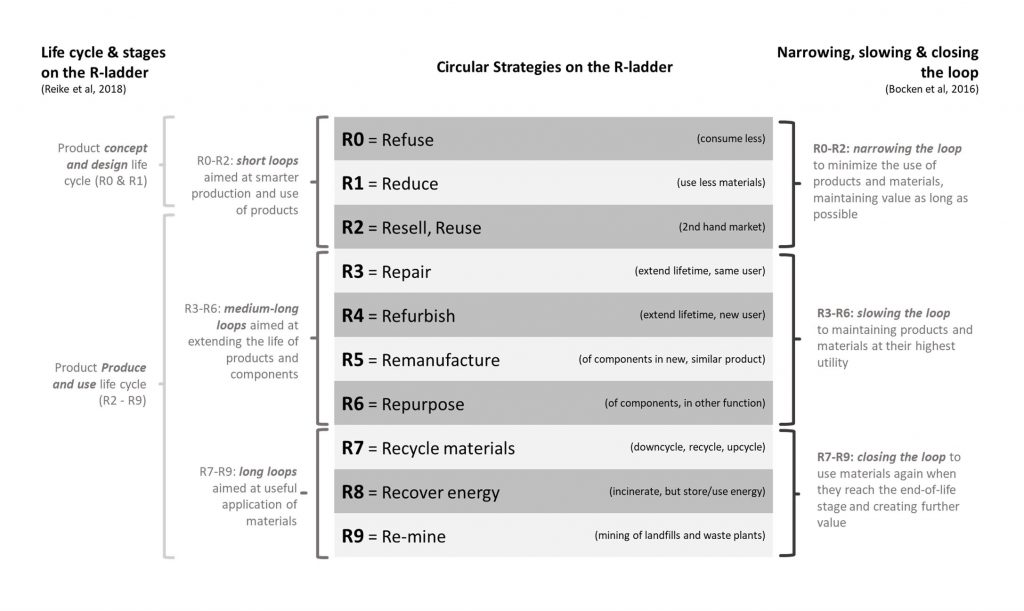

- Circularity: the different practical strategies for achieving circular flows, applicable in a practical way by companies, captured by the 10-R framework, specifying hierarchical levels R0 to R9, applied to both the Concept and Design cycle, as well as the Produce and Use cycle (Reike et al, 2018).

The strategies for achieving circularity

Value retention refers to the idea of resources carrying an intrinsic value, opposed to the economic notions of value. In terms of finished goods this means retaining their state or reusing them with as little change as possible to ensure consecutive lives, and in the case of the conservation of resources retaining them closest to their original state (Reike et al, 2018).

For those who are already a bit familiar with the circular economy, the letter ‘R’ must already sound familiar. Most concepts related to circular strategies have ‘re-‘ in the naming: reuse, refurbish, recycle and so on. ‘Re-’ in Latin means ‘again’, ‘back’, but also ‘afresh’, which all point to the essence of a circular economy (Sihvonen & Ritola, 2015).

These strategies are referred to as the R-ladder or the R-imperatives. There are ten strategies on the R-ladder: refuse, reduce, resell/reuse, repair, refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, recycle materials, recover (energy) and re-mine. The strategies all have different implications for resource use, design, manufacturing, consumer usage and the afterlife stage. The first two strategies are the preventive options – R0 refuse and R1 reduce – and the other eight strategies are the reutilization options. The rule of thumb for the R-ladder is the higher up the ladder you go (from R0 to R9), the more resources are used, thus the higher the environmental burden, and the least circular they are.

The 10R’s are divided into 3 stages:

- Stage 1 – R0 to R2: short loops aimed at smarter production and use of products by refusing, reducing or reselling/reusing. We also call this narrowing the loop contributing to minimize the use of products and materials, maintaining value as long as possible (Bocken et al, 2016). A great example is Antwerp based jeans brand HNST jeans. They eliminate the use of any toxic chemicals (refuse), and use less virgin materials by creating jeans with 56% recycled content, emitting 76% less CO2, using 82% less water (reduce).

- Stage 2 – R3 to R6: medium long loops aimed at extending the lifespan by repairing, refurbishing, remanufacturing or repurposing products and components. We also call this slowing the loop contributing to maintaining products and materials at their highest utility. Central here is value retention and value addition to products and parts. For example, producing a skateboard from used bottle caps like Dutch brand WasteBoards, or producing and repairing bicycles with the remanufactured parts of old ones, like in the Blue Connection Game.

- Stage 3 – R7 to R9: long loops focussed on useful application of materials by material recycling, (energy) recovery and re-mining. We also call this closing the loop to use materials again when they reach the end-of-life stage and creating further value. These materials would otherwise be lost by being burned or landfilled. Here, the energy put forward by incinerating residual waste is used as city heating, or, like Black Bear Carbon, end-of-life tires are recycled into inks and coatings.

Important to remember is that these 10 strategies can be implemented by businesses and within value chains simultaneously. Usually there is one dominant circular strategy, and one or more of other strategies can be applied as a complement to the chosen dominant strategy.

Why the circular economy is here to stay

Our current global challenges highlight the importance of resilience: the ability to survive shocks and live through disruptions such as a pandemic, water scarcity, or other climate change related crisis. It is essential to create a more resilient system that ensures the health and safety of all people. A system in which we reframe our relationship with the natural world and in which where we are stronger in the face of future challenges. A system where we are less dependent on global intertwined supply chains. A system where creativity, cooperation and transparency are central. And that system is circular.

Flanders Circular and VITO (2020) conducted a resilience survey studying how various organisations experienced the COVID-19 crisis and how they look to the future. The study highlights three success factors that make companies more resilient to disruption, which are all fundamental in a circular economy:

- Renewed focus on local and connected business

- Creativity

- Cooperation

Besides, 34% of circular companies experienced shortage compared to 98% of ‘business-as-usual’ companies. The circular strategies that lead to fewer shortages appear to focus mainly on local, short supply chains and less material use. This study shows that circular strategies do not only make companies more sustainable, they also make them more resilient. It seems fair to say that circular economy is here to stay.

About the Author:

Rozanne Henzen is a researcher and circular economy expert within the Sustainable Transformation Lab (STL) of Antwerp Management School, based in Antwerp, Belgium. She is currently recognized as one of the Sustainable Young 100 of 2020 in the Netherlands.

Ed Weenk and Rozanne Henzen just launched a new book called ‘Mastering the Circular Economy’. Mastering the Circular Economy is an introduction to circularity from a business and value chain management perspective. Want to know more? Check out our book page here.

The authors hosted an exclusive event on ‘Design a course on Mastering the Circular Economy’. They presented a concrete example of how you can implement a circular economy course with the textbook Mastering the Circular Economy. You can watch it here.

By incorporating business simulation game, The Blue Connection, as an integral part of the book, the reader can immediately put theory to practice. At Inchainge, we are confident that this publication will set a new standard for textbooks on Circular Economy and bring the integral learning experience with The Blue Connection to the next level.

References

Bocken, N et al (2016) Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308-320.

Circle Economy. (2021). The Circularity Gap Report 2021. Retrieved on April 28 2021, from https://www.circle-economy.com/resources/circularity-gap-report-2021

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2012). Towards the Circular Economy: economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. Retrieved on April 28 2021, from https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/TCE_Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation_9-Dec-2015.pdf

Flanders Circular & VITO. (2020). Dossier Veerkracht. Retrieved on April 25 2021, from https://www.vlaanderen-circulair.be/nl/veerkracht

Flapper, S D P. (1995). One-way or reusable distribution items?, Working Paper, Eindhoven University of Technology, https://research.tue.nl/files/4425561/436114.pdf

Global Preparedness Monitoring Board. (2019). A world at risk. Retrieved on April 25 2021, from https://apps.who.int/gpmb/assets/annual_report/GPMB_Annual_Report_English.pdf

Reike, D, Vermeulen, W and Witjes, S. (2018). The circular economy: New or Refurbished as CE 3.0? – Exploring controversies in the Conceptualization of the Circular Economy through a focus on History and Resource Value Retention Options. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 135, 246-264, Retrieved on April 28 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344917302756

Sihvonen, S, Ritola, T (2015) Conceptualizing ReX for aggregating end-of-life strategies

in product development. Procedia CIRP 29, 639–644.

Webster, K. (2017). The circular economy: a wealth of flows (2nd edition). Cowes, Isle of Wight: Ellen MacArthur Foundation Publishing.

Weetman, C. (2016). A Circular Economy Handbook for Business and Supply Chains. Repair, Remake, Redesign, Rethink. London: Kogan Page.

World Economic Forum. (2019). The Global Risks Report 2020. Retrieved on April 25 2021, from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2020

Rozanne Henzen

Rozanne Henzen