testimonials

The essence of

supply chain management by Léo Ducrot

Supply chain management is about creating the operating model the company needs to realize its business strategy. It requires to make sure that all the actors of a company are working in the same direction. The Fresh Connection is the perfect tool to understand, experience, and observe the power (and challenges) of alignment. It is a very good learning experience and a lot of fun

Léo Ducrot

Léo DucrotSupply Chain Planning Expert at OMP

“What is supply chain management (and why is it different from logistics)?” I open my training introduction to supply chain concepts with this question. After giving this training many times, it appears to me that defining supply chain management is a challenge, even for experienced practitioners and trained people. I later give my audience the following academically accepted definition: Supply chain management is the organization and management of the flows of information, material, and financials to ultimately fulfill customer needs. This definition gives a good idea of the scope, but it does a poor job at capturing the essence of supply chain.

As part of their master in supply chain management, MIT organizes a competition based on the serious game The Fresh Connection. This is how in October 2019, I flew to Athens to attend the final round of the international competition of the Fresh connection with 3 other classmates and dear friends. We won the different rounds and scored 3rd in the global final without any advanced models. Where many groups developed complex Excels we showed up in Athens with a scattered Excel. We would discuss a lot to align every part of our “company” into a consistent system supporting and enabling our strategy. I believe this endless quest for alignment is the essence of supply chain. The fresh connection is the perfect tool to understand, experience, and observe the power of alignment.

Supply chains are complex dynamic systems

Someone once told me “solving a problem in a supply chain creates 5 other problems…”. This because supply chains consist of many parts that interact in a non-linear fashion. They are complex dynamic systems by nature. I believe supply chain practitioners have much to learn from system dynamics, the science of complex dynamic systems.

“Solving a problem in a supply chain creates 5 other problems…”

Supply chains are actually made of multiple dynamic systems that work together (Procurement, inventory management, manufacturing, distribution, etc.). This is a typical structure that is commonly called a hierarchical system. System dynamic shows the vital importance to align the goals of the different subsystems. Most of the failures and inefficiencies of hierarchical systems come from misaligned objectives between the subparts. Misalignments usually come from the use of intermediate goals or proxies. If we think about the manufacturing part of the company. Its role is to produce the goods consumers want, but it needs to do it well. The company seeks to produce profits; therefore, the manufacturing must produce at the lowest possible costs. It makes perfect sense that the industrial manager actively works at reducing costs. But what if the company, let us call it Company A, makes money from selling fast-moving products on a volatile market? In this case Company A will soon be in trouble because cost-centric approaches will reduce the responsiveness and kill the source of profit of the company… In this case, the error is to link profits to low costs and not to flexibility. For Company A, order fulfillment or time to market are better goals for the industrial manager. The cost-centric approach pushes for large batches and efficient (rigid) operations, while time-to-market goals will chase small lot sizes and high responsiveness.

This small example also sheds light on a fundamental truth: Sales and supply chains are inter-connected, and they should work together! The company must define its business strategy. In this exercise, the company defines what is the value proposition of the company and what are the targeted customers. The supply chain must ensure that the operations (sourcing, manufacturing, distribution) support and enable this business strategy. It also means that the sales team must focus on customers that fit the operating model. As Jonathan Byrnes says “It’s hard to focus and align your company when your sales compensation system tells your sales reps that all revenue dollars are equally desirable.”1 If the supply chain team made a terrific job creating a very efficient (low cost) operating model but the sales reps keep coming with small orders to reach their targets, then the company will have a hard time dealing with these small volatile orders.

“Sales and supply chains are inter-connected, and they should work together!”

When the intermediate objectives do not add up it will create stress and oscillations in the priorities. Most people who have work in operations know and have experienced the regular shift of priority between cost (or inventory) reduction and service level. A system thinker will quickly realize that these oscillations can lead to an erosion of the goals. Basically, since the company cannot achieve high service levels and low costs, they will start to reduce their ambition. This is how in a couple of years a company can go from ambitious targets of 98% service level for a cost of $50 per part to celebrating a good year with 92% service level and parts at $65. They gradually lowered their expectations to the point that they lost track of the original targets. It is interesting to notice that if the company focused on service level they could probably achieve 98% service level and a part at $55-60. Oscillations and misaligned goals do not only lead to missed targets, but they also make it worse in all aspects. For the story, our strategy in the Fresh connection was to have high service levels. At some point, they offered the opportunity to expand to 3 new markets. At the end of the game, we were one of the very few to serve all these markets even if volume was not the main target. Many groups that adopted a volume-based strategy could not serve these markets. Alignments create a virtual circle of performance, but misalignments drag down all parts of the company (given a long enough time horizon).

Navigating the trade-offs

Let us discuss how to create alignment or strategic fit at scale. The trick here is to realize that all supply chain decisions, and to some extent all business decisions, are trade-offs. For insistence, a company can choose to generate profits with large volumes and low marginal profits, or a company can choose to get profits with high marginal profits and low volume. It is unlikely to be able to hold both high marginal profits and high volume for long. Such a business will soon attract competitors that will halt this heaven.

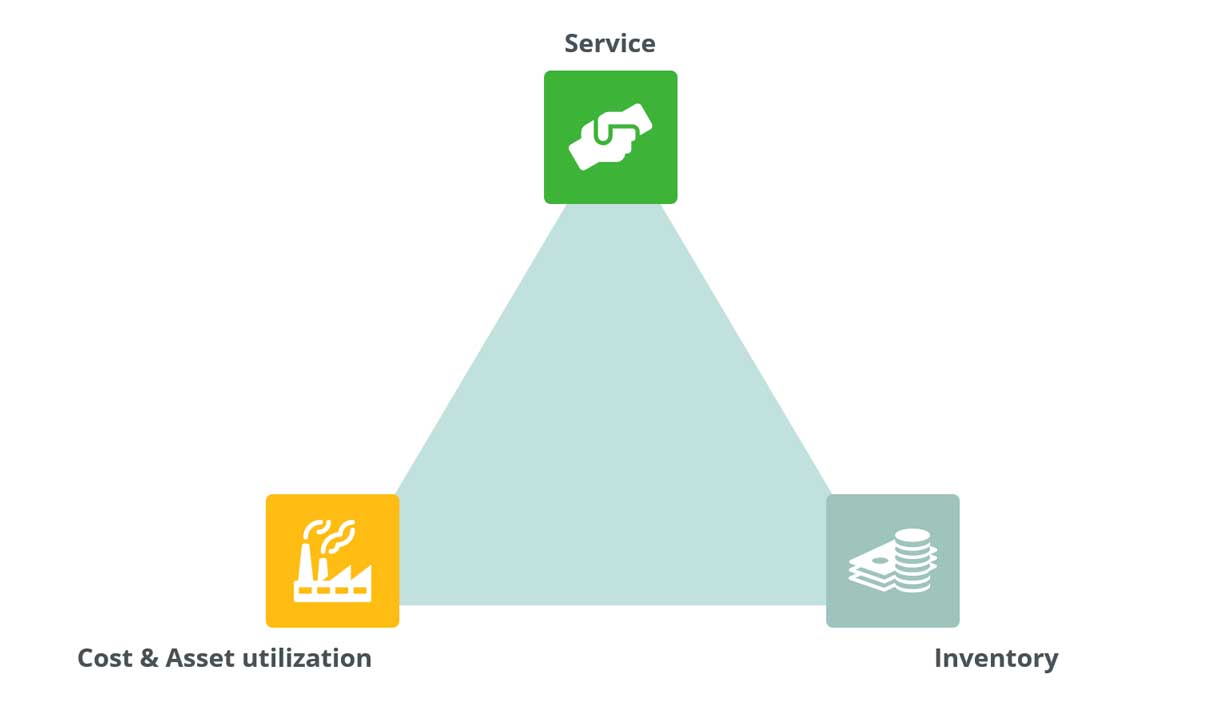

There is a classic tool to represent the main trade-off any supply chain must deal with. The supply chain triangle is a fundamental tool that can help companies to define how they want to operate.

The short story is that company should pick one corner, optimize it against a second corner and use the last one as a buffer. For example, it is possible to aim at high service levels with low inventory. It requires having a comfortable capacity buffer. (This is typically how a Kanban system operates). Chasing multiple corners simultaneously weakens any competitive advantage and leads to weak priorities management. Surprisingly, only a few companies can give a clear answer to the way to operate. The supply chain team usually can answer the question, but the rest of the company just doesn’t care because it is ‘supply chain stuff’. By now it should be clear that for Company A (from the previous section) to be successful, the manufacturing system and the transportation must be flexible, the sourcing responsive and the supply chain agile. They must focus on the top corner, and more precisely all parts of the company must focus on the top corner.

“The objectives must act as a compass to navigate the trade-off”

Trade-offs are everywhere. Large production batches reduce costs (assuming that everything is sold without discount…) but they come with higher working capital and with lower flexibility. Full truckloads have the same trade-off of reducing costs to the expense of working capital (longer lead times due to longer waiting time to get full truckload) and flexibility. Many people believe that cost-cutting actions happen in a vacuum and will not change the rest of the system. Many times, it is not true and these actions will alter the flexibility or the responsiveness of the supply chain. If we exaggerate a little bit, we can boil it down to this: ‘Every decision is a trade-off, and in any trade-off, there is only one direction that supports the business strategy’. The objectives of the department (manufacturing, sourcing, etc.) must act as a compass to navigate the trade-off. The supply chain strategy must make sure that the goals of all departments aggregate to a consistent system.

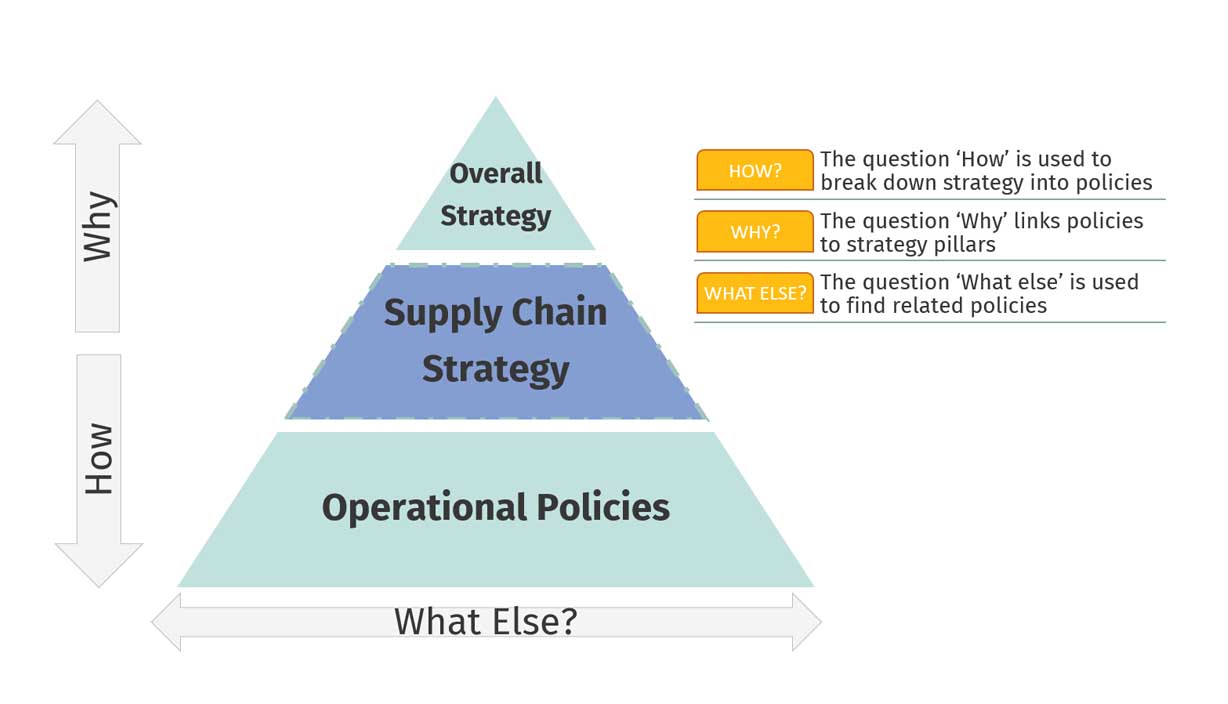

If we take a step back, I basically said so far that operations must follow the business strategy. More precisely I said that, if done right, the supply chain strategy can act as a bridge between the corporate strategy and the operation policies. It can make sure that the forklift operators and the truck operators are working toward the corporate strategy. This is what Dr. Roberto Perez Franco from the MIT Supply Chain Strategy Lab argued in 2016 in the report "Rethinking your Supply Chain strategy"2.

The essence of supply chain

So, what is the essence of supply chain management? The essence of supply chain management is to create and maintain alignment between the corporate strategy and the operations on the ground. It must create the operating model the company needs to realize its business strategy.

“Supply chain management is about creating the operating model the company needs to realize its business strategy.”

Understanding this will help to define what part of the operations must be optimized and what part must be managed as buffers or enablers. It also appears that ‘best practices and ‘benchmarks’ should be handled with great care. Bram Desmet discusses this topic in depth in his recommended book supply chain strategy and financial metrics3. An effective solution for one company may not work (or be a disaster) for another one. A particularity of complex dynamic systems is that the same action can produce very different results.

Sources

1. “Islands of profit in a sea of red ink” by Jonathan L. S. Byrnes. Portfolio/Penguin, 2010

2. “Rethinking your Supply Chain strategy” by Dr. Roberto Perez Franco. MIT Supply Chain Strategy Lab, 2016

3. “Supply Chain Strategy and Financial Metrics: The Supply Chain Triangle Of Service, Cost And Cash” by Bram Desmet. KoganPage, 2018.

UTi Puts Itself in its Customers’ Shoes

Logistics service supplier UTi aims to offer its customers integrated solutions that go beyond merely organising transport. Therefore, it decided to train its entire global sales team in S&OP – a process which logistics service providers would not normally bother with. The training method used: The Fresh Connection

DuPont takes Employees out of their comfort zone

DuPont runs several training sessions around the world to increase its managers’ awareness of the importance of internal cooperation and leadership. One key component of these five-day sessions is business game The Fresh Connection, which helps the chemical company to combat ‘silo thinking’.